An Invisible Tsunami: ‘Aging Alone’ and Its Effect on Older Americans, Families, and Taxpayers

Social capital may be most valuable when an individual’s needs are greatest. Old age is a time of life when people often need to rely on family, friends, and other social relationships for care they are no longer able to provide for themselves. If an elderly adult lacks those relationships, however, they may have to lean more heavily on paid professional care, potentially leading to a lower quality of life and higher costs for families and government.

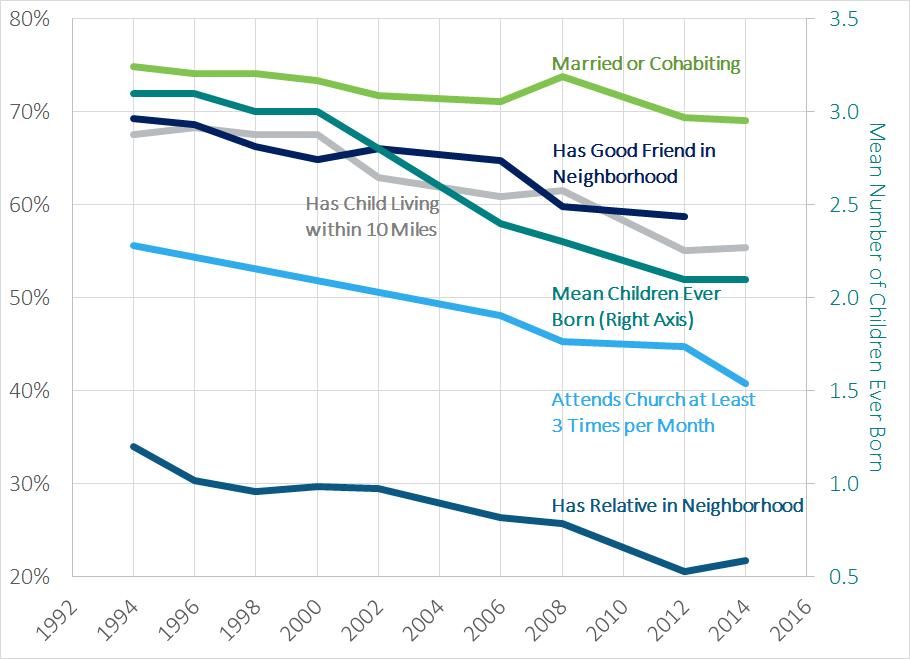

Robert Putnam of Harvard University, author of the landmark study Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, highlighted the looming problem of “aging alone” during a May 2017 Joint Economic Committee hearing.1 He noted that although many people are aware that the nation faces caretaking challenges due to the sizable increase of its elderly population, few are aware of how declining social capital may exacerbate these challenges. As Putnam pointed out, the elderly often receive much of their care informally, including from family members, friends, and community organizations.2 However, a variety of social capital indicators suggest a weakening of associational life among Americans. As such, baby boomers and subsequent generations of Americans may enter old age with fewer social ties than did Americans born earlier in the twentieth century. That would mean fewer informal caregivers. To assess this possibility, we examined data from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS), conducted by the University of Michigan.3 The HRS is a set of surveys of adults ages 50 and older in the United States that began in 1992. We examined trends in social capital over a 20-year period—1994 to 2014—among adults ages 61 to 63 years of age.4 The oldest cohort in our study was thus born between 1931 and 1933, while the youngest cohort was born between 1951 and 1953 (during the baby boom).

Social Support among Adults Ages 61-63, 1994-2014

Source: Health and Retirement Study, http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/.

The results of our analyses, shown in the above chart, confirm that older Americans in the future are unlikely to have the level of support from caregivers that they enjoyed in the past. The share of retiring adults who are living with a spouse or cohabiting with a partner has fallen from about 75 percent to 69 percent, reflecting declining marriage rates and higher divorce rates, which more than offset falling widowhood, rising cohabitation, and growing life expectancy.5 Retiring adults today are also less likely to have children who can take care of them. In 1994, two-thirds (68 percent) of retiring adults lived within ten miles of an adult child. That share fell to 55 percent in 2014. In large part, this decline reflects falling fertility. The right axis of the figure indicates that the average number of children ever born to retiring adults fell from 3.1 in 1994 to 2.1 in 2014.

Against these declines (and not shown in the figure), retiring adults today have more living siblings than their counterparts had 20 years ago. Nevertheless, they are less likely to have a relative living nearby. The share of retiring adults with a relative in their neighborhood (outside their home) fell from 34 percent in 1994 to 22 percent in 2014. They also have fewer friends close at hand; the share with a good friend in the neighborhood fell from 69 percent to 59 percent between 1994 and 2012 (the last year for which comparable data are available).6 Finally, retiring adults may have fewer social connections outside their neighborhood than in the past. The share who attend religious services at least three times per month fell from 56 percent to 41 percent between 1994 and 2014.7 Of course, social support might come from acquaintances based in non-religious institutions and organizations. However, as Putnam writes in Bowling Alone,

Faith communities in which people worship together are arguably the single most important repository of social capital in America….nearly half of all associational memberships in America are church related, half of all personal philanthropy is religious in character, and half of all volunteering occurs in a religious context.8

Our analyses affirm estimates from Putnam’s research. According to his projections, social support in old age may decline by roughly one-third between the generation born in 1930 and that born in the mid-1950s (who were in their early 60s between 1991 and today).

The decline in the availability of support from family, friends, neighbors, and congregants among retiring adults has implications for future retirees, caregivers, and taxpayers. Surviving HRS respondents who were between the ages of 61 and 63 in 1994 are in their mid-80s today. Those 61 to 63 in 2014 will reach that age in 2038. In between, we are likely to see an increasingly inadequate level of informal care, even as greater survival rates increase the need for care.

For retirees, that would necessitate a greater amount of institutional care outside the home and away from loved ones, reducing, for many, their quality of life. There are also financial implications for the elderly and their families. While care provided informally creates costs such as the lost wages of caregivers, institutional care often entails burdensome expenses. Medicaid, for instance, is the primary payer of nursing home expenses, but to qualify for assistance, Americans routinely spend down their assets (or, in the case of adult children, their parent’s assets). Paying the cost of long-term care privately is prohibitively expensive for many families.

Finally, the decline in social capital among the elderly, by increasing demand for institutional care, is likely to worsen federal and state deficits. Current projections of spending on Medicare and Medicaid inadequately account for declining social support; they implicitly assume that the mix of informal and formal care that today’s older Americans receive will stay the same over time. Putnam roughly estimated in his hearing testimony that the inflation-adjusted cost of paid elder care could double by 2030 over the level that would exist under the assumption that social support holds steady.

The good news is that by anticipating these potential costs, we can prepare for and reduce them. Policymakers, health care providers, and institutions of civil society should think creatively about how to mitigate the looming challenge—starting now. And today’s prime-age and retiring adults must consider how to balance immediate needs, future plans, and the need for someone to take care of older Americans. Unfortunately, in an age of declining social capital, our collective quiver will be short of arrows as we search for ways to address these questions.

Endnotes

1 Hearing on the State of Social Capital in America, 115th Congress (2017) (statement of Robert D. Putnam, Malkin Professor of Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School), accessed November 20, 2018, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/222a1636-e668-4893-b082-418a100fd93d/robert-putnam-testimony.pdf

2 Much of Putnam’s work was done in collaboration with Chaz Kelsh, a graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School.

3 Health and Retirement Study, accessed November 20, 2018, http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/.

4 We utilized data from the 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2012, and 2014 surveys. We selected the age range 61 to 63 to maximize the number of surveys from which we could obtain data while avoiding complicating issues of changing mortality. Each survey includes different birth cohorts. Importantly, we do not look at multiple age groups within any one survey to examine trends, since doing so would conflate period, cohort, and age effects. The 61- to 63-year-old age range was unavailable in the 1992 data. Furthermore, we do not include respondents who were in a nursing home. The percentage of 61-63-year-old adults in a nursing home was small, with a high of around 1 percent in 2002 and a low of 0.05 percent in 2014.

5 Renee Stepler, “Led by Baby Boomers, divorce rates climb for America’s 50+ population,” Pew Research Center, March 9, 2017, accessed November 20, 2018, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/09/led-by-baby-boomers-divorce-rates-climb-for-americas-50-population/. Susan L. Brown and I-Fen Lin, “The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults, 1990-2010,” Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 67, no. 6, 731-741. Renee Stepler, “Number of U.S. adults cohabiting with a partner continues to rise, especially among those 50 and older,” Pew Research Center, April 6, 2017, accessed November 20, 2018, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/06/number-of-u-s-adults-cohabiting-with-a-partner-continues-to-rise-especially-among-those-50-and-older/; and Susan L. Brown and Matthew R. Wright, “Marriage, Cohabitation, and Divorce in Later Life,” Innovation in Aging 1, no. 2, September 2017: 1-11. Valerie King and Mindy E. Scott, “A comparison of cohabiting relationships among older and younger adults,” Journal of Marriage and Family 67, no. 2, May 2005: 271-285.

6 This question was administered differently in 2014 than in previous waves of the survey, and the difference in administration appears to have made the 2014 result noncomparable to earlier years. In the 2014 wave, this question was not asked of the entire sample, but rather a sub-sample of respondents through a “leave-behind” questionnaire. Furthermore, in 2014 this question was only asked of individuals who indicated that they had any friends. Despite being noncomparable to other years, the 2014 result is consistent in that it shows a trend of decline in the percent of 61-63-year-olds reporting that they have a good friend in the neighborhood.

7 In the 1994 wave, only respondents who indicated a religious preference were asked about their frequency of religious attendance; however, in subsequent waves of the survey, all participants were asked about frequency of religious attendance regardless of whether they had a religious preference. In order to make the 1994 religious attendance variable comparable to the other waves, we thus included those who said they had no religious preference in that wave among those who attend religious services less than three times per month.

8 Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), p. 66.